What is Paroxysmal Nocturnal Haemoglobinuria (PNH)?

The medical information provided on this website is by way of general guidance only. You should always contact your clinician for medical advice and do not rely upon the information provided here.

Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) is a rare disease affecting between approximately one and two people in every one million and affects both men and women at different ages. PNH is an ‘acquired’ genetic disease, so it cannot be inherited and patients are usually diagnosed in young adulthood.

red blood cells

PNH is a bone marrow failure disorder where abnormal blood cells can emerge from the bone marrow lacking multiple GPI- anchored proteins as a result of a genetic defect (mutation) in the “PIGA” gene. Absence of these proteins leave the blood cells unprotected against a series of complex reactions called “complement activation” which is part of the body’s normal immune response to fight infections. As a result, the red blood cells are destroyed (haemolysis) which is the main cause of PNH symptoms and complications.

aplastic anaemia

PNH is often diagnosed with aplastic anaemia although patients can have one without the other. Treatment for aplastic anaemia is different from PNH and will depend on whether it is inherited or acquired.

Not everyone who has PNH is affected by it in the same way. Some people may have no symptoms and others may have many as well as other complications.

It is possible for PNH to disappear however this is not very common.

There is no cure yet for PNH, however there are successful treatments which can alleviate the symptoms.

signs and symptoms

There can be a large variation in the signs and symptoms of PNH both between patients and in the same patient at different times.

Some people exhibit no symptoms and others may be affected by a number of very different ones as well as complications.

Patients with no or few symptoms can still suffer from complications. Over time, the symptoms experienced by a PNH patient can change. Some patients only experience symptoms when an episode of severe haemolysis is occurring (which is usually triggered by an infection) and others may experience symptoms all the time. A list of possible symptoms include: abdominal and back pain, anaemia, blood clots, breathlessness, bruising, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), erectile dysfunction, fatigue, jaundice, kidney damage and haemoglobinuria (dark or red urine caused by free haemoglobin as a result of destruction of red blood cells).

diagnosis

How is PNH diagnosed?

Despite the fact that PNH patients who have access to treatment are in an enviable position, the “diagnostic odyssey” which affects rare diseases generally, equally applies to PNH. General Practitioners and haematologists need to be able to recognise a disparate set of symptoms, such as anaemia, stomach and back pain, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), jaundice, breathlessness, erectile dysfunction, severe fatigue and dark or red coloured urine.

Misdiagnosis

As not all patients experience all these symptoms and especially, perhaps the most telling one, dark/red coloured urine, the recurrent stomach pain can send patients down a urology and/or gastroenterology pathway for years at a time. Anorexia has been another misdiagnosis resulting from weight loss due to difficulty swallowing as a result of the dysphagia (which results from the free haemoglobin from the damaged red cells binding and removing nitric oxide). Complications caused by PNH prior to diagnosis can lead to irreparable damage which is why diagnosis and/or referral to a PNH specialist in a timely manner, is vital.

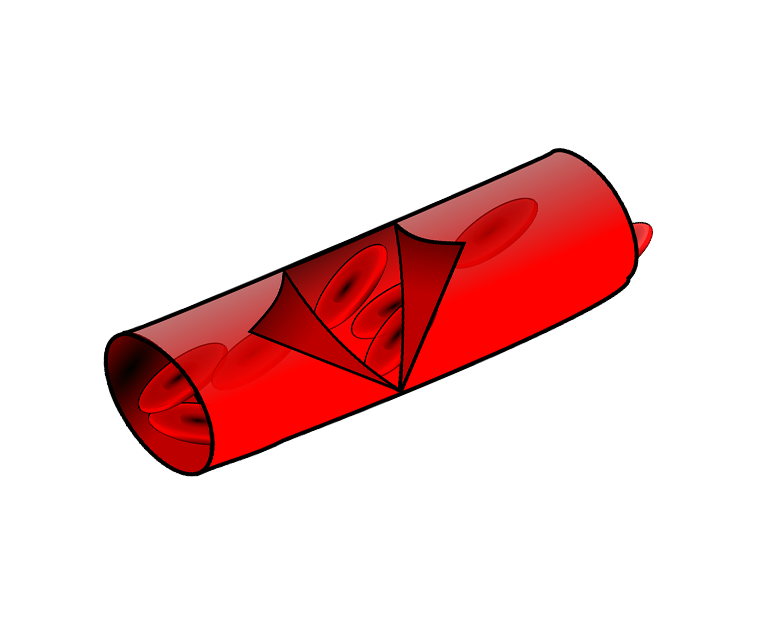

Blood sample

To confirm a diagnosis of PNH, a blood sample can be sent to a specialist laboratory to check whether it contains any PNH blood cells using a test called “flow cytometry”. This shows the percentage of red and white PNH cells in the blood. It is more accurate for white blood cells during or just after an episode of haemolysis or a blood transfusion.

There are different treatments that those living with PNH may require. Some people, especially those with a small PNH clone may require little or no treatment.